Arguably, this year’s Biennale is the most political in many years. Climate change, social justice, housing, equity and inclusion, and the diaspora in many different versions are featured not only in the two main exhibitions curated by Ghanaian Scottish architect and educator, Lesley Lokko, but also in many of the national pavilions. That the national pavilions take the cue of the Biennale curator is not always the case – and some appear as if Lokko’s words have made little to no difference to what they chose to present. But some have and allow me to share a few of my favorites.

Brazil, deservedly in my view, won the Golden Lion for the best national pavilion. Titled “Terra” the exhibition turns to practices of African and indigenous origin, recognized today as Brazilian heritage. Using drawings, maps, and a powerful video installation the first gallery called “De-colonizing the Canon” questions the canonical narrative that Brasilia was built in the middle of nowhere and highlights the forceful removal of the Indigenous and Quilombola inhabitants from the site to make place for the new capital. The second gallery, “Places of Origin, Archaeologies of the Future” brings to light projects and practices of Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian knowledge that connect social and ecological reparation in a way rarely seen.

From the Brazilian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

From the Brazilian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

From the Brazilian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

In various ways, different forms of displacement and diaspora are discussed in both the Australian, the Canadian, and the Nordic pavilions.

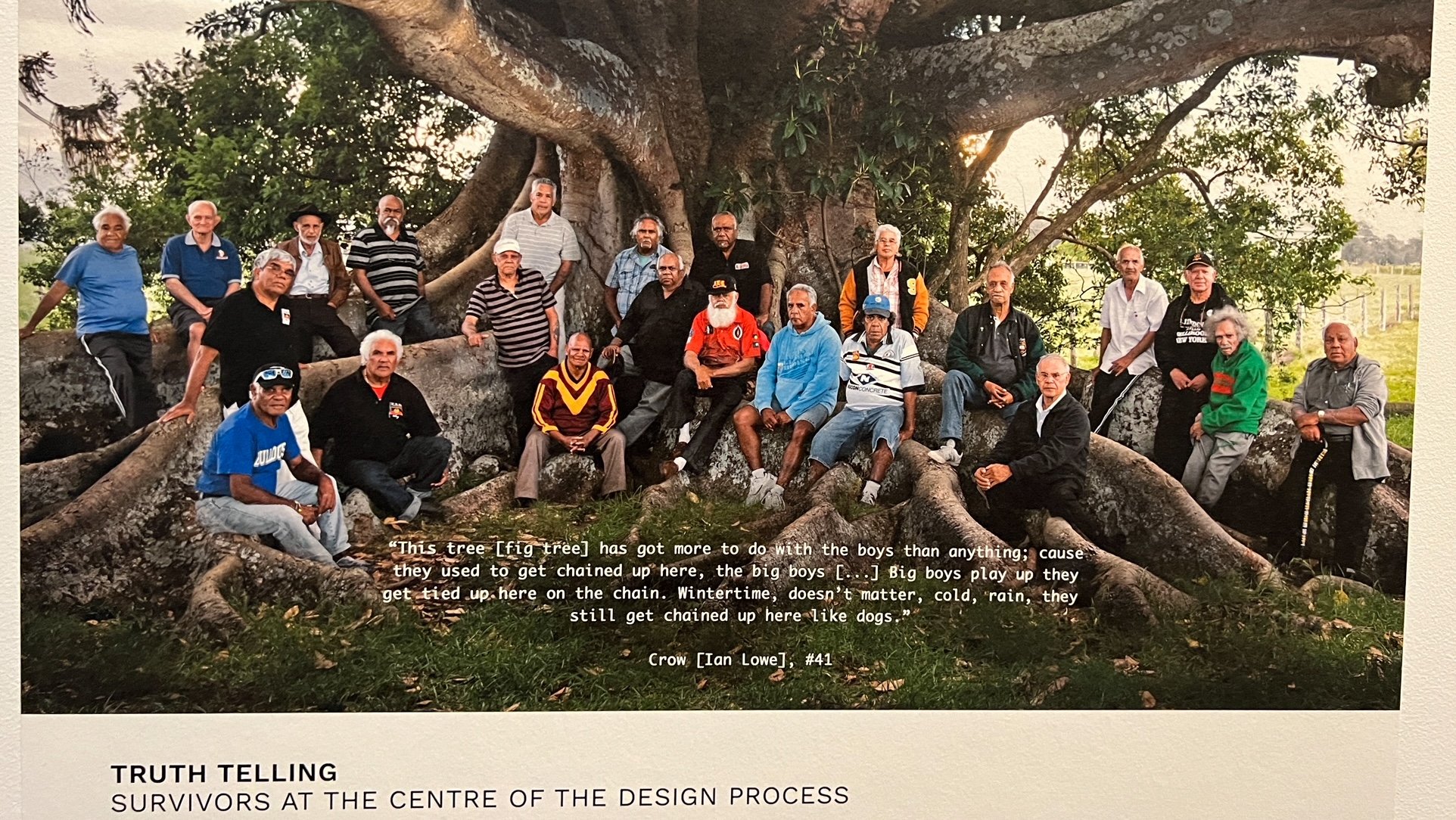

The Australian exhibition, “Unsettling”, participates in the “questioning and reimagining” of Australia’s colonial inheritance using sound, video, a replica of the arched belvedere from the Empire Hotel, and an open archive of tactics to decolonize architecture.

From the Australian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

From the Australian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

The Canadian pavilion has been turned in to a living, activist workshop that discusses the “housing alienation” that started when European settlers arrived in Canada and “violently took land away from Indigenous peoples” and attacked Indigenous ways of knowing and doing.

From the Canadian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

From the Canadian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

Finally, the beautiful Nordic Pavilion, designed by Norwegian architect Sverre Fehn in 1962, has been filled with “Girjegumpi”, a nomadic collaborative library of Sami art, films, tools, and more, embracing topics such as Sami architecture and design, traditional and ancestral knowledge, and activism.

From the Nordic pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

From the Nordic pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

Several pavilions deal with sustainability and with water in particular – Denmark, Holland, Greece, Argentina, Portugal, and Panama for example. My favorite among the water themed pavilions is the Egyptian exhibition, NiLab, a collaboration between Ain-Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, and the Mediterranea University of Reggio Calabria, Italy, and 24 international universities, charged to discuss possible futures for the hugely historical Nile. It is a simple yet evocative exhibition using city and water sounds, a wide-screen video journey on and along various parts of the Nile, a boat like sculpture, and a large table clad with a historic map and exhibiting simple booklets containing the student projects.

From the Egyptian pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

From the Egyptian pavilion - sometimes a simple layout is better. (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)

As always, the scale of the Venice Architecture Biennale is overwhelming. Even the three days I spent walking the national pavilions and the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, the exhibitions in the Arsenale, and visiting some of the many parallel activities and exhibitions around the city of Venice, does not do justice to the effort and energy so many people, organizations and countries pour into this event.

Patrick Schumacher, of Zaha Hadid Architects, recently summed up his impression of a visit to the Venice Architecture Biennale in a Facebook post saying “There is nothing in sight here…” He suggested the term “architecture” be removed from the title of the show, since no architecture, according to Schumacher, is exhibited. “Only the Chinese pavilion shows architecture, plenty of architecture” said Schumacher, and added that the single other exception is the work on display by Adjaye Associates, adding “I did not find Francis Kéré's display.”

About the rest of the huge Venice Architecture Biennale, Patrick Schumacher simply states: “What’s the point of all this? Is it meant to inspire conversations? Architects want to talk about (and see) architecture. They won't talk about decolonising xyz.”

In her introduction to the exhibition, curator Lesley Lokko had already addressed this and made it clear that “All participants in this Biennale Architettura speak from the richly creative ‘both/and’ position that is specific to those who occupy more than one identity, speak more than one language, or speak from locations long considered outside the centre. We have deliberately chosen to frame participants as ‘practitioners’, not ‘architects’ and/or ‘urbanists’, ‘designers’, ‘landscape architects’, ‘engineers’ or ‘academics’ because it is our contention that the rich, complex conditions of both Africa and a rapidly hybridising world call for a different and broader understanding of the term ‘architect’.”

All I can say is that Patrick Schumacher is wrong when he says there is no architecture at the Venice Biennale and wrong also when he claims architects do not wish to engage in decolonization. Not only do many architects from all over the world show a lot of architecture in the form of projects and solutions to important challenges. The Biennale also raises the level of our shared architectural consciousness and helps us rediscover and reconnect with a host of repressed, forgotten, or displaced architectural knowledge and practices from ‘outside the centre’ that (hopefully) will help transform how we view and practice our field moving forward.

Kudos, Lesley Lokko!

Henning Martin-Thomsen, Arkitekt MAA, Int’l Assoc. AIA, MMD (CBS)

Publisher and contributor to AIA International Communication & PR Committee

From the Nordic pavilion (Photo: Henning Martin-Thomsen)